The rebound effect is overplayed

by Kenneth Gillingham, Matthew J. Kotchen, David S. Rapson, and Gernot Wagner

Introduction:

Buy a more fuel-efficient car and you will spend more time behind the wheel. That argument, termed the rebound effect, has earned critics of energy-efficiency programmes a voice in the climate-policy debate, for example with an article in The New York Times entitled 'When energy efficiency sullies the environment'.

The rebound effect idea — and its extreme variant the 'backfire' effect, in which supposed energy savings turn into greater energy use — stems from nineteenth-century economist Stanley Jevons. In his 1865 book The Coal Question, Jevons hypothesized that energy use rises as industry becomes more efficient because people produce and consume more goods as a result.

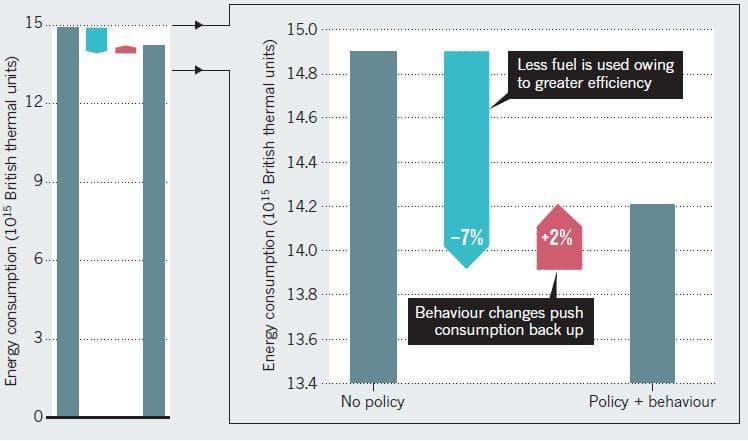

The rebound effect is real and should be considered in strategic energy planning. But it has become a distraction. A vast academic literature shows that rebounds are too small to derail energy-efficiency policies. Studies and simulations indicate that behavioural responses shave 5–30% off intended energy savings (see 'Bounce back'), reaching no more than 60% when combined with macroeconomic effects.

There is ample scientific evidence to diminish undue concern about rebounds and bolster support for energy-efficiency measures.

Full text: "Energy policy: The rebound effect is overplayed"