The Race to Power Data Centers

Columbia Business School Climate Knowledge Initiative

My columns, essays, books, as well as research and teaching materials like case studies.

Columbia Business School Climate Knowledge Initiative

Constructing the Low-Carbon Future

by Kent D. Daniel, Robert B. Litterman, and Gernot Wagner

by Romain Fillon, Manuel Linsenmeier and Gernot Wagner

by Till Requate, Gernot Wagner, and Israel Waichman

Ending reliance on oil, coal, and gas, and embracing technologies that will only improve and become cheaper over time, is not just smart climate policy. It is the best way to improve economic competitiveness and human prosperity for decades to come.

by Miranda Hack, V. Faye McNeill, Dan Steingart, and Gernot Wagner

Deutschland hat es versäumt, eine konsequente Energiepolitik für die Zukunft zu machen. Stattdessen lähmt eine übervorsichtige Industriepolitik den Wandel. So bleibt man abhängig – von China und den USA.

Coalbed methane is an underappreciated problem of global steel production. While cutting methane emissions in the steel supply chain will not produce green steel overnight, it could reduce the sector’s emissions by the equivalent of a billion tons of carbon annually, and at little cost.

Columbia Business School Case

Columbia Business School Climate Knowledge Initiative

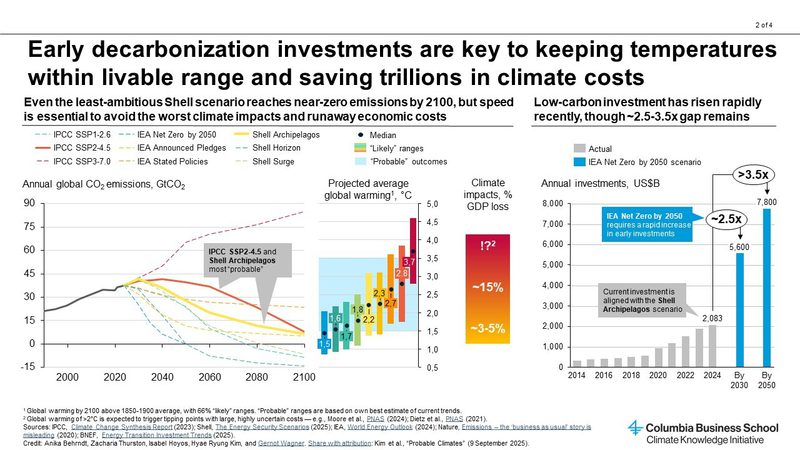

A net-zero world by 2100 is likely inevitable, but the next decade will be critical for securing a livable future.

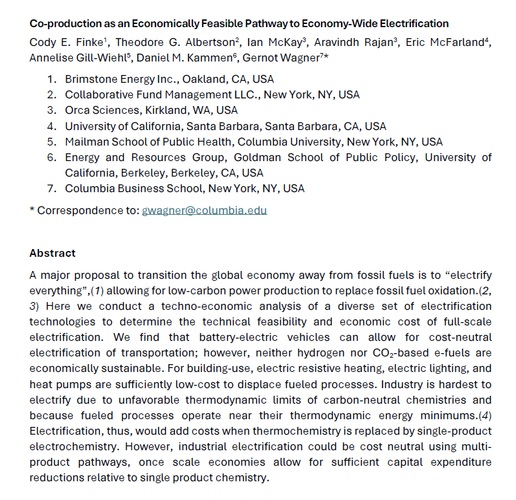

by Cody E. Finke, Theodore G. Albertson, Ian McKay, Aravindh Rajan, Eric McFarland, Annelise Gill-Wiehl, Daniel M. Kammen, and Gernot Wagner

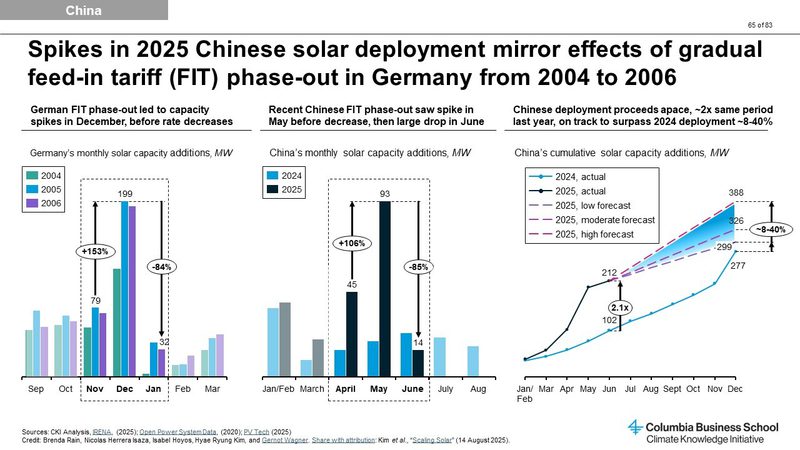

China’s Solar PV installations dropped 85 percent in June after a planned subsidy phase-out. But far from a retreat from renewables, the country's energy policy reforms reflect an increasingly mature and competitive solar industry.

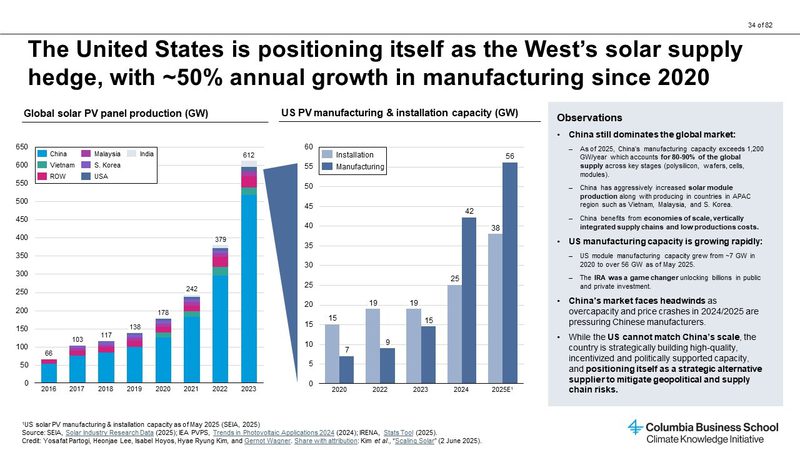

If political conditions in the United States and elsewhere require a rebranding of technologies formerly known as “climate tech,” so be it. The larger economic, technological, and geopolitical forces propelling everyone toward cleaner energy remain as strong as ever.

Financial Times business school teaching case study

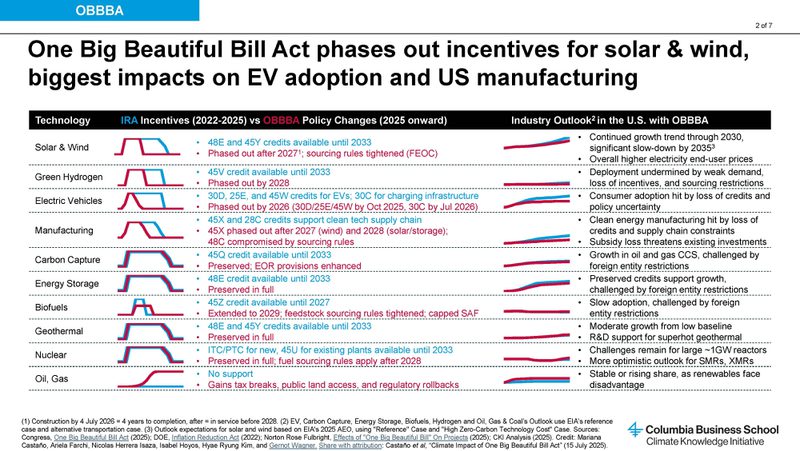

While the OBBBA guts renewable energy incentives, undercuts US manufacturing, and hands a long-term advantage to China, economics will continue to drive clean energy growth.

Despite the administration’s push for fossil fuels, solar is faster, cheaper, more stable, and increasingly American-made. Here’s why it’s the smartest path to true energy leadership.

by Mark Freeman, Ben Groom, Frikk Nesje, and Gernot Wagner

Financial Times business school teaching case study