U.S. Environmental and Health rules pay for themselves—and then some

The regulations’ benefits outweigh their costs. That means we’re not maximizing their potential.

On Monday, a Florida judge overturned the federal mask mandate on public transportation. Although the Biden administration may appeal the ruling, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) almost immediately stopped requiring masks on planes and trains. Major airlines, Amtrak and other transportation companies like Uber and Lyft soon followed suit. Cue the inevitable cries of joy and dismay as some pilots announced midair that passengers could take off their masks.

Now, I’m not here to tell you whether or when you should wear a mask. There will always be some risk in not wearing one. Sometimes that risk might be worth taking, at other times not. While some Covid-19 health protocols have always been more about hygiene theater than real protection, it’s also clear that masks work, protecting both the wearer and those around them.

That, of course, was the calculus behind mask mandates in the first place—and it applies by extension to almost any kind of rule or regulation. If private benefits alone justify an action, there may be no need for the government to step in. If private benefits and costs point one way but public ones another, the situation calls for the government to set rules and pass laws to guide us.

That leads directly to benefit-cost analysis, which has its own advantages and some very real shortcomings. To adapt a quote from Winston Churchill, it’s the worst way to decide on policies except for all the others. It forces analysts to make heroic assumptions, sometimes asking them to quantify the unquantifiable. As a result, it is often biased. For example, with regard to public works projects like the construction of roads and bridges, benefits are often overestimated and costs are underestimated. Still, done right, benefit-cost analysis has important uses.

For major rules affecting public health and environmental outcomes, including climate change, the biases by and large go the other way. Cutting pollution has so many benefits that it’s hard to quantify them all. It’s difficult for scientists to establish the link between pollutants and impacts on health, and for economists to translate those impacts into dollars. Actual benefit estimates, then, are often best thought of as a conservative lower bound. The costs, meanwhile, are typically assumed to be higher than they turn out to be, since analyses are based on current rather than better and, thus, cheaper future technologies. Compliance with most rules is typically less costly than it’s assumed to be at the time the rule is passed.

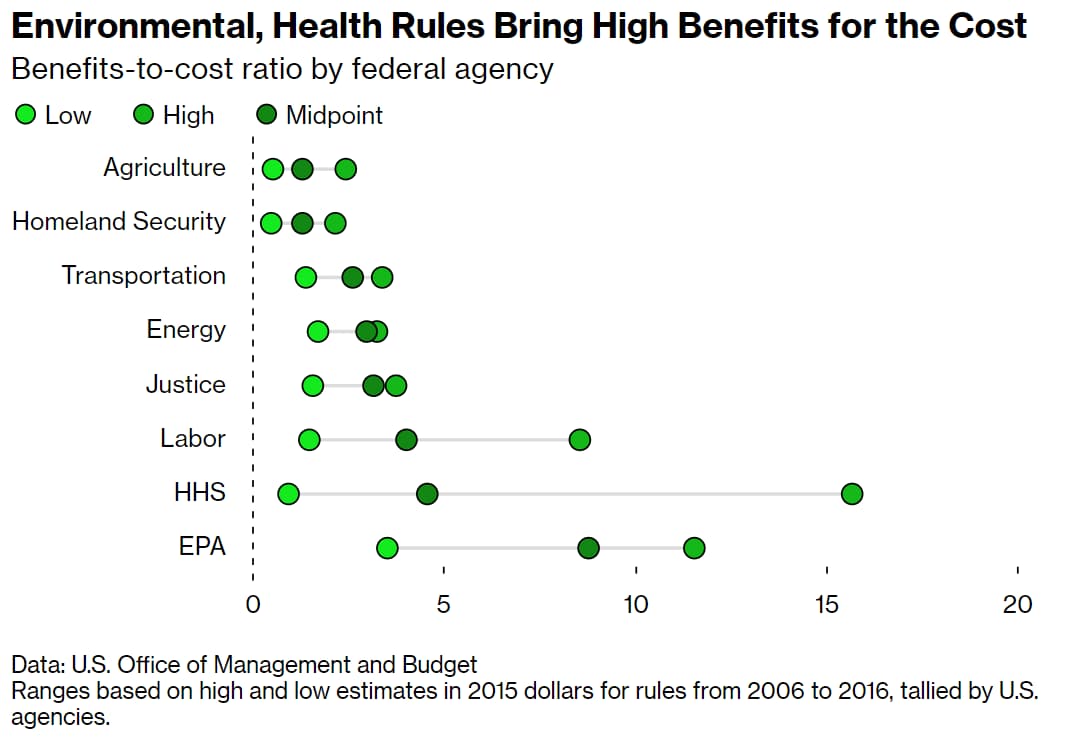

A full benefit-cost analysis for mask-wearing and Covid prevention would be tough to do, and I won’t pretend to know how to do it. What I do know, courtesy of the White House Office of Management and Budget and its reports, is that there are systematic differences in this ratio across federal agencies.

When comparing major agency rules on a simple ratio of benefits to costs, those adopted by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHSA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) come out on top, and that’s been true now for at least two decades. Near the bottom, with ratios that are close to 1-to-1: rules from the departments of Agriculture and Homeland Security.

That doesn’t mean those agencies’ rules don’t pay off. Potentially wasteful spending notwithstanding, benefits still exceed costs, almost by definition, because otherwise the rules wouldn’t have been passed in the first place.

But it does mean that, when it comes to agriculture or homeland security, we may have squeezed out almost every remaining dollar of net benefits. Think of the TSA forcing us all to take off our shoes when we go through airport security because of that one failed attempt years ago to hide a homemade bomb in a shoe.

The areas of health and the environment, meanwhile, have a lot more potential for rules and regulations that would provide ample benefits: climate and clean air rules, or public health provisions. High benefit-cost ratios, therefore, aren’t necessarily a good sign. They show how much further we have to go, and that the U.S. government is simply not doing enough on that front.

Gernot Wagner writes the Risky Climate column for Bloomberg Green. He teaches at Columbia Business School (on leave from New York University). His latest book is Geoengineering: the Gamble (Polity, 2021). Follow him on Twitter: @GernotWagner. This column was first published by Bloomberg Green on April 22nd, 2022, and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.