Helping people hurt from high energy prices

Hint: Reducing them isn’t the answer.

Energy prices are through the roof as Russia continues its war against Ukraine. It’s all too tempting for governments the world over to attempt to lower them directly. Doing so, however, is a mistake. Not because people don’t need help: They do. But lowering the cost of each gallon or liter of gasoline, each cubic foot or meter of natural gas, or each kilowatt hour of electricity is mistaken, in more ways than one.

It’s rare to be able to point to Economics 101 to give the full picture of how to address a particular policy challenge—and how not to. This is one of those instances.

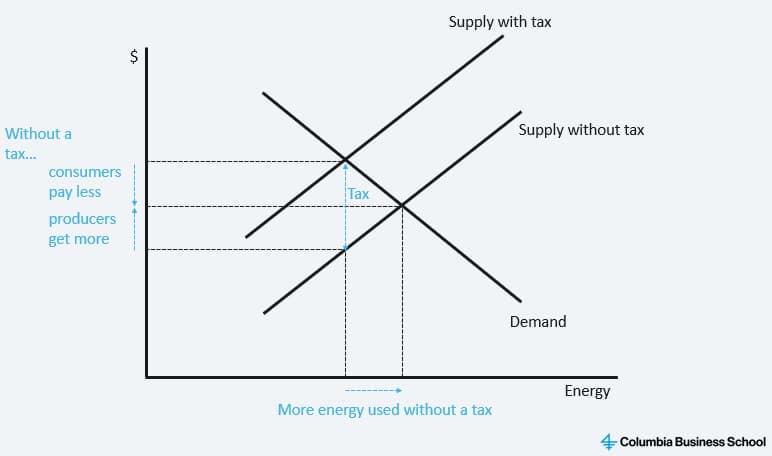

Taxes and other regulations drive a wedge between what consumers pay and what producers get. That wedge comes with its own costs. It also has some clear benefits. For one, fossil energy use comes with massive external costs, from local air pollution to climate change. That calls for governments to step in and put a price on otherwise unpriced consequences of energy extraction, transportation and use.

With energy prices spiking, governments are inclined to provide relief via direct subsidies or various forms of tax holidays. The trouble is that doing so sets the wrong incentives. High energy prices tell consumers to use less of that particular form of energy, and they tell producers to look for alternative supplies. Artificially lowering energy prices has the exact opposite effect.

Removing a tax lowers prices for consumers, encouraging them to use more energy. It also raises prices to producers, increasing their total revenue. Russian President Vladimir Putin can only thank each Western government attempting to provide relief to its citizens by lowering energy taxes. Europe is spending hundreds of millions of dollars each day on Russian gas alone.

What to do instead? One answer is to increase taxes specifically on Russian oil, gas and coal. That would help support Western governments’ broader sanctions. It would hurt Putin’s war effort. But it would not provide relief to consumers dependent on Russian energy.

That relief should come in form of direct cash payments. The key part: Do not link them to energy use. Austria just passed energy subsidies lowering the cost of each kilometer driven, each cubic meter of gas burned, and each kilowatt hour of electricity consumed, in a package worth €1.3 billion. Instead of these kinds of subsidies, the Austrian government should have simply given each of its 4 million households a €325 check. The rich will not need the money. The poor household will likely get more relief this way than via artificially lowered energy bills. Given that the rich will not need the money, there are indeed better ways to target relief—but whichever form it takes, it must not be tied to energy use.

California’s rebate of $400 per registered car isn’t tied to each mile driven, at least. But it only benefits drivers, not those who have arranged their lives in the Golden State to live without a car, either by necessity or by choice. Much better then to give the same $400 to each resident, regardless of whether they own a car. [Update on 4 July 2022: California did change its plans, making the rebate no longer contingent on owning a car.]

There are other direct measures aimed at lowering energy demand, from subsidizing public transit to encouraging working from home, since it reduces the energy used in commuting and heating office buildings. All of this should have been done five weeks ago, immediately after the invasion. But better late than never. The key insight behind all these measures: Actually lower energy demand. Don’t encourage its use in the midst of a fossil-fueled war.

Gernot Wagner writes the Risky Climate column for Bloomberg Green. He teaches at Columbia Business School (on leave from New York University). His latest book is Geoengineering: the Gamble (Polity, 2021). Follow him on Twitter: @GernotWagner. This column was first published by Bloomberg Green on April 1st, 2022, under the title "The Right Way to Help People Hurting From High Energy Prices," and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.