Going Green but Getting Nowhere

Don’t stop recycling. Don’t stop buying local. But add mastering some basic economics to your to-do list.

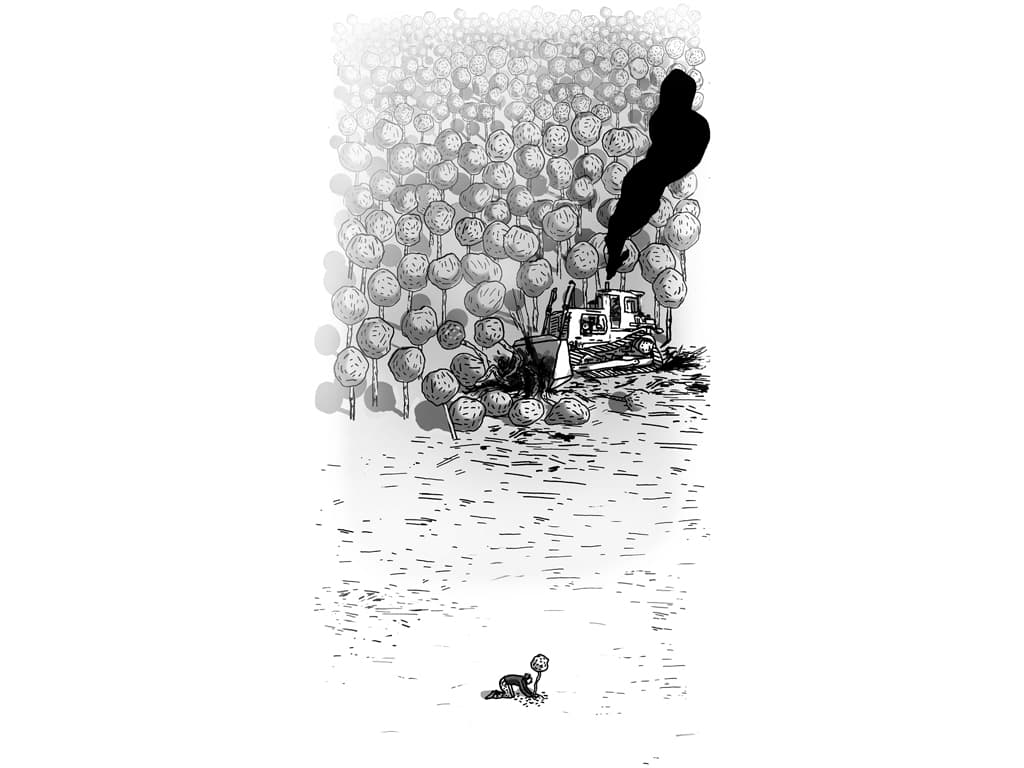

Leif Parsons/New York Times

YOU reduce, reuse and recycle. You turn down plastic and paper. You avoid out-of-season grapes. You do all the right things.

Good.

Just know that it won’t save the tuna, protect the rain forest or stop global warming. The changes necessary are so large and profound that they are beyond the reach of individual action.

You refuse the plastic bag at the register, believing this one gesture somehow makes a difference, and then carry your takeout meal back to your car for a carbon-emitting trip home.

Say you’re willing to make real sacrifices. Sell your car. Forsake your air-conditioner in the summer, turn down the heat in the winter. Try to become no-impact man. You would, in fact, have no impact on the planet. Americans would continue to emit an average of 20 tons of carbon dioxide a year; Europeans, about 10 tons.

What about going bigger? You are the pope with a billion followers, and let’s say all of them take your advice to heart. If all Catholics decreased their emissions to zero overnight, the planet would surely notice, but pollution would still be rising. Of course, a billion people, whether they’re Catholic or adherents of any other religion or creed, will do no such thing. Two weeks of silence in a Buddhist yoga retreat in the Himalayas with your BlackBerry checked at the door? Sure. An entire life voluntarily lived off the grid? No thanks.

And that focuses only on those who can decrease their emissions. When your average is 20 tons per year, going down to 18 tons is as easy as taking a staycation. But if you are among the four billion on the planet who each emit one ton a year, you have nowhere to go but up.

Leading scientific groups and most climate scientists say we need to decrease global annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least half of current levels by 2050 and much further by the end of the century. And that will still mean rising temperatures and sea levels for generations.

So why bother recycling or riding your bike to the store? Because we all want to do something, anything. Call it “action bias.” But, sadly, individual action does not work. It distracts us from the need for collective action, and it doesn’t add up to enough. Self-interest, not self-sacrifice, is what induces noticeable change. Only the right economic policies will enable us as individuals to be guided by self-interest and still do the right thing for the planet.

Every ton of carbon dioxide pollution causes around $20 of damage to economies, ecosystems and human health. That sum times 20 implies $400 worth of damage per American per year. That’s not damage you’re going to do in the distant future; that’s damage each of us is doing right now. Who pays for it?

We pay as a society. My cross-country flight adds fractions of a penny to everyone else’s cost. That knowledge leads some of us to voluntarily chip in a few bucks to “offset” our emissions. But none of these payments motivate anyone to fly less. It doesn’t lead airlines to switch to more fuel-efficient planes or routes. If anything, airlines by now use voluntary offsets as a marketing ploy to make green-conscious passengers feel better. The result is planetary socialism at its worst: we all pay the price because individuals don’t.

It won’t change until a regulatory system compels us to pay our fair share to limit pollution accordingly. Limit, of course, is code for “cap and trade,” the system that helped phase out lead in gasoline in the 1980s, slashed acid rain pollution in the 1990s and is now bringing entire fisheries back from the brink. “Cap and trade” for carbon is beginning to decrease carbon pollution in Europe, and similar models are slated to do the same from California to China.

Alas, this approach has been declared dead in Washington, ironically by self-styled free-marketers. Another solution, a carbon tax, is also off the table because, well, it’s a tax.

Never mind that markets are truly free only when everyone pays the full price for his or her actions. Anything else is socialism. The reality is that we cannot overcome the global threats posed by greenhouse gases without speaking the ultimate inconvenient truth: getting people excited about making individual environmental sacrifices is doomed to fail.

High school science tells us that global warming is real. And economics teaches us that humanity must have the right incentives if it is to stop this terrible trend.

Don’t stop recycling. Don’t stop buying local. But add mastering some basic economics to your to-do list. Our future will be largely determined by our ability to admit the need to end planetary socialism. That’s the most fundamental of economics lessons and one any serious environmentalist ought to heed.

Gernot Wagner is an economist at the Environmental Defense Fund and the author of the forthcoming “But Will the Planet Notice?”

Published in The New York Times on September 8th, 2011.