Early Investment in Decarbonization Can Help Save Trillions in Climate Costs

A net-zero world by 2100 is likely inevitable, but the next decade will be critical for securing a livable future.

By Anika Behrndt, Isabel Hoyos, and Gernot Wagner

Decarbonization by 2100 is all but certain, but the next decade will be key to avoiding even worse climate outcomes and saving trillions in climate costs.

Fast-falling clean technology costs and rising private investment mean that despite recent retreat from climate action by countries like the United States, the energy transition is inevitable, if not imminent.

Clean innovation is moving faster than anticipated: Over the past decade, the cost of solar photovoltaic systems has dropped by 90 percent, onshore wind by 70 percent, and batteries by more than 90 percent. Just the past 18 months saw another 50 percent drop in battery costs.

Even in countries where political momentum around climate action is inconsistent, deployment continues. In the United States, despite partisan gridlock, the Solar Energy Industry Association projects nearly 43 GW of new solar energy capacity to be added annually through 2030, indicating the energy transition is now driven at least as much by fundamental market forces as by political will, or lack thereof.

Meanwhile, evidence shows that oil and gas companies are less eager to expand drilling than political narratives suggest, indicating shifts in long-term investment strategy.

Climate Scenarios: What the Next Century Could Look Like

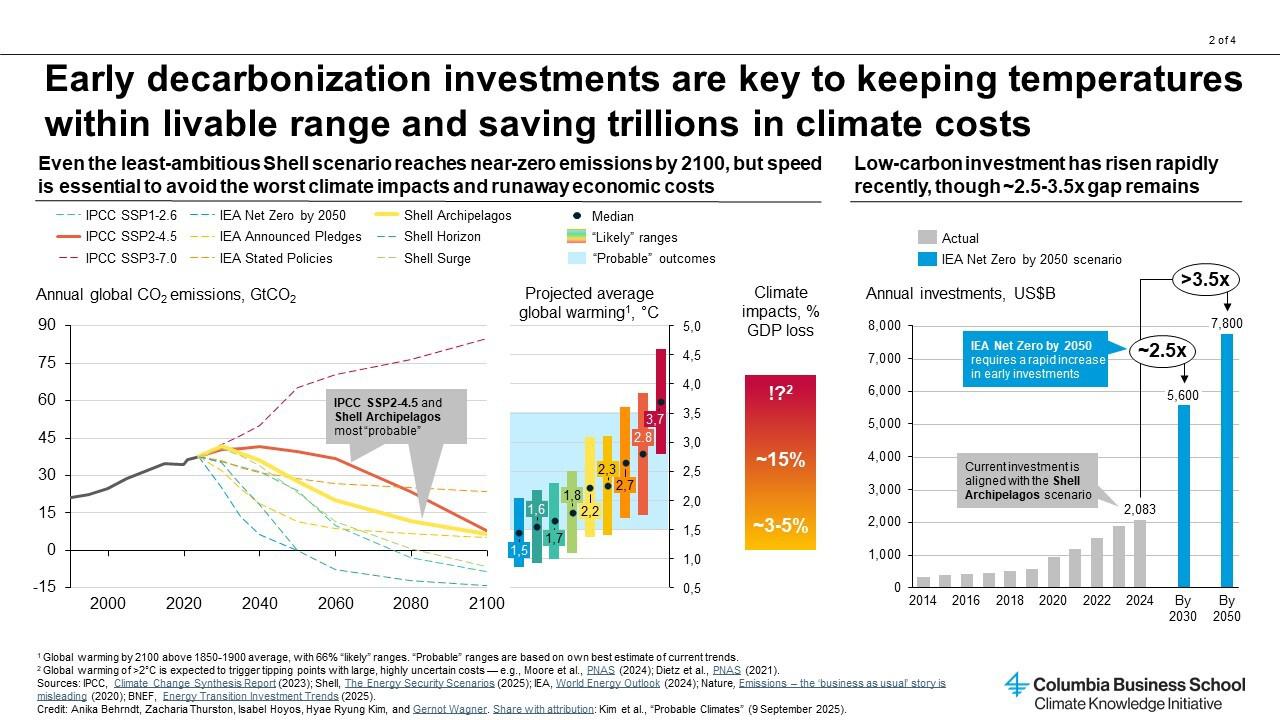

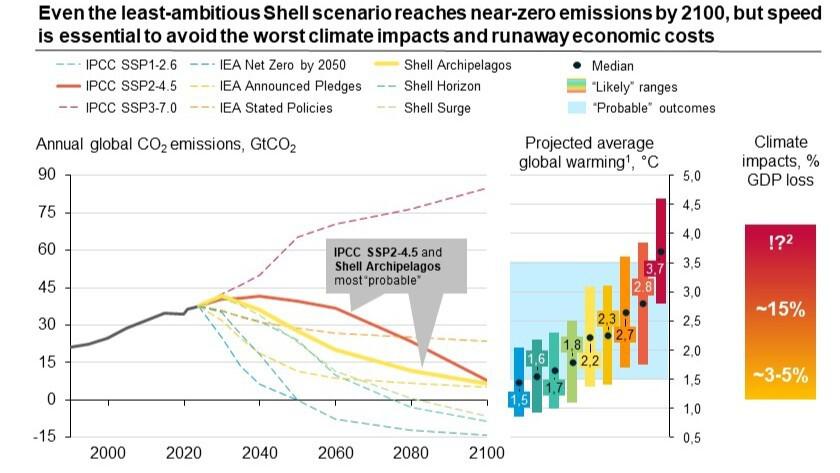

It is, of course, impossible to predict precisely how governments, markets, and people will behave, but a wide range of possible climate scenarios all point to the same conclusion: near-global decarbonization by the end of the century.

Even the fossil fuel industry now acknowledges this trajectory. In fact, Shell’s own climate scenarios project net-zero emissions by 2100 in even the least-ambitious pathway. While its models rely heavily on the development of carbon capture and storage, a technology that remains largely unproven at scale, CCS itself is largely a bridge to a fully decarbonized future by 2100. But the world cannot afford to wait that long.

The real question is how decarbonization can be accelerated to happen within 25 or 30 years, rather than 70 or 75. And the speed and scale of action in this decade are key.

Once hopeful scenarios like the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Net Zero by 2050 are now highly unlikely, given the current trajectory of policy and resulting emissions.

On the opposite extreme, worst-case scenarios like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) SSP3-7.0 scenario, which suggests the world may not manage to decarbonize at all this century, are equally unlikely. They contradict fundamental technological and economic trends.

The most probable scenarios lie somewhere in the middle, like the IPCC’s SSPS2-4.5 and Shell’s Archipelagos scenarios. Neither scenario paints a particularly hopeful picture, however. Both anticipate global net-zero emissions only around the end of the century and rely on continued fossil fuel use through mid-century, with Shell assuming greater reliance on CCUS and a slightly more systemic transition.

Neither path aligns with limiting warming to 1.5°C, but somewhere in the 2.2 to 2.8°C range. These pathways reflect the reality of current policies and market inertia, meaning much more needs to be done to limit the costs of unmitigated climate change.

Why Every Degree of Global Warming Matters

What is known for certain is that climate change is real, human driven, and already affecting lives — especially those in marginalized communities.

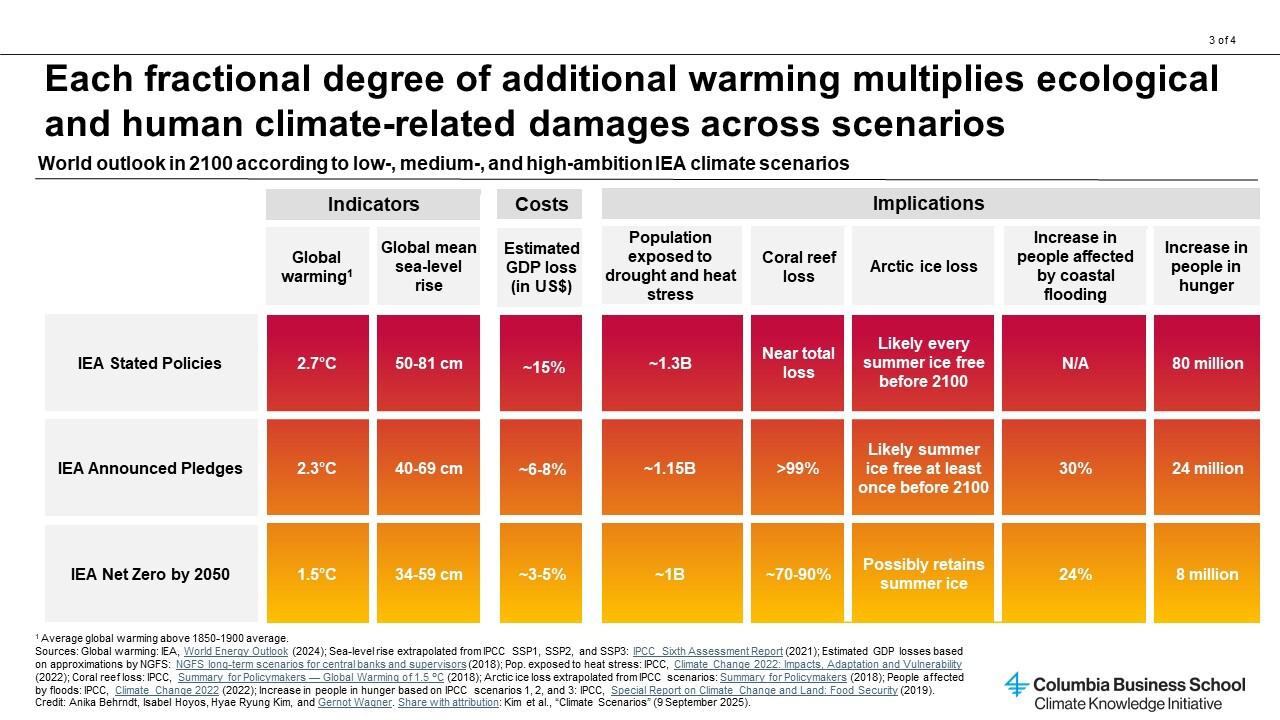

The scale and pace of investment in decarbonization will shape the world we live in for decades to come. IPCC has long been tallying the large and rising costs of climate change, and IEA’s own summary of the effects is equally dramatic.

The world has a narrow but critical window to influence how far we overshoot global warming and how severe the consequences will be. Climate modeling makes it clear that the difference between warming by 1.5°C, 2°C, and 3.5°C or more over pre-industrial average temperatures is the difference between a livable planet and an uninhabitable one.

Climate-economic estimates differ widely, but they are clear that the costs of global warming are large and increasing rapidly with each fraction of a degree. That’s why near-term decisions are so critical. Every year without strong mitigation action locks in additional emissions and narrows the chance to avoid the most damaging climate outcomes.

Clean Energy Investment Is Surging, Led by China

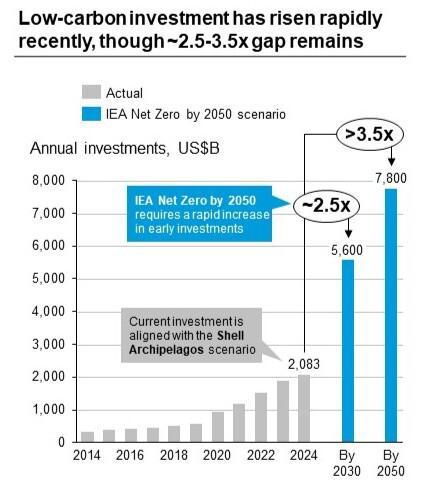

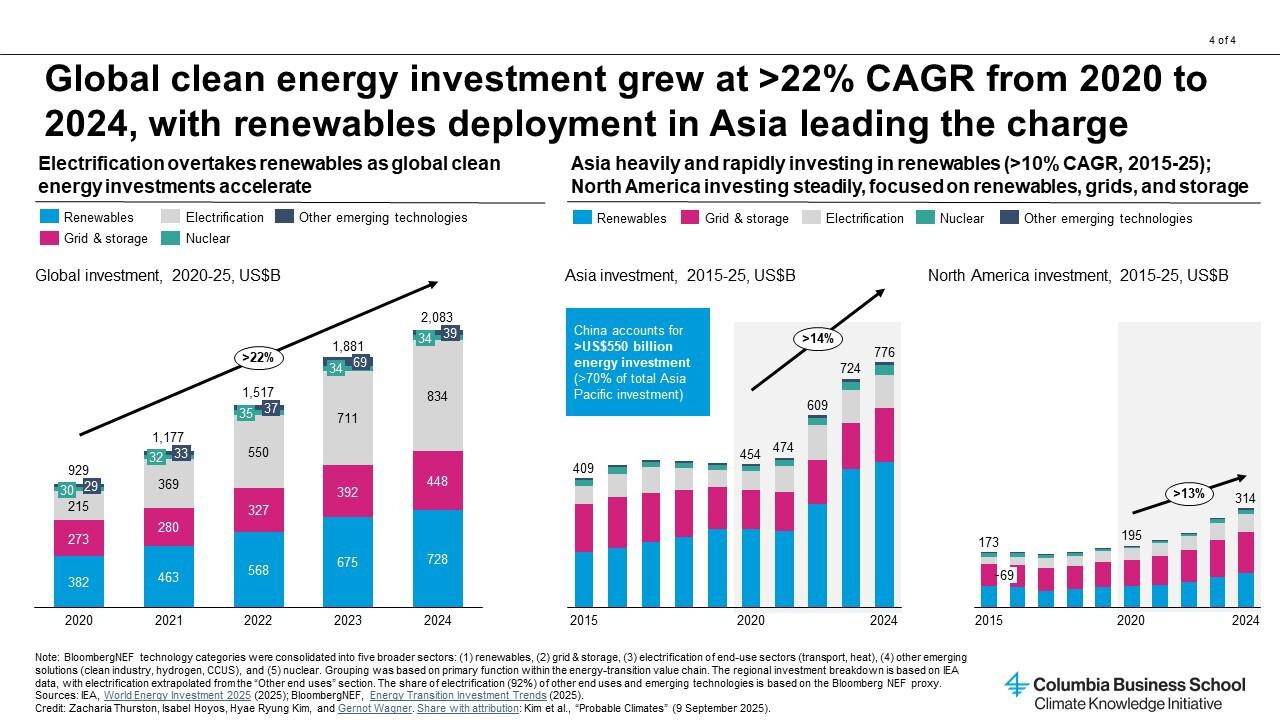

Global clean energy investments last year topped $2 trillion for the first time. That marks a rapid increase, well over 20 percent per year for the past half-decade. The trend is pointing in the right direction, yet the need is still much greater.

IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario asks for around 2.5 times as much spending in the near term, by 2030, with a further significant increase by mid-century.

The investments are not equally distributed. Asia has seen a rapid ramp-up in clean energy investments. China alone accounts for nearly 70 percent of last year’s Asian investments, over $560 billion, making it the largest clean energy investor in the world.

North America, by comparison, grew from $173 billion in 2015 to $314 billion in 2024 (>13 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR)), with a balanced focus on renewables, grids, and storage, but still invests at less than 40 percent of China’s level.

The key now is speed. The sooner these investments are made, the earlier emissions are cut, the more damages we avoid, and the less adaptation needed later.

Why the Path to Decarbonization Matters as Much as the Goal

Beyond the scale and speed of climate investment, the direction of that capital is equally decisive. Successful deployment will depend on whether financial flows are strategically aligned with high-impact mitigation pathways or diverted into technologies and systems that merely extend the lifetime of carbon-intensive infrastructure.

Comparable scenarios by the IEA and Shell have fundamentally distinct transition logics. While IEA scenarios emphasize a rapid deployment of renewables, electrification of end-use sectors, and broad efficiency gains, Shell scenarios place significant weight on carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) to preserve existing fossil fuel assets well into the second half of the century.

This divergence is worth highlighting because allocation determines whether capital accelerates a structural shift away from fossil dependence or enables a slower transition under the guise of technological optimism. Overreliance on CCUS, particularly in sectors where cleaner alternatives already exist, risks entrenching delay rather than delivering meaningful emissions reductions.

Moreover, climate investment strategies must be tailored to regional, sectoral, and technological contexts. Targeted, near-term deployment of proven solutions, alongside support for innovation where gaps remain, is essential to convert high-level targets into measurable progress. Without clear prioritization, the promise of decarbonization risks being undermined by inertia.

The question is no longer whether the world will decarbonize but how quickly and through which pathways it will do it. The choices made this decade will be the difference between a warmer but resilient Earth or a planet already plagued by irreversible damage by the time we reach net zero.

With the technologies largely in place and capital beginning to move, the opportunity is clear: Align investment with impact, act decisively, and ensure the transition delivers not just cleaner energy but a safer, fairer future.

This article includes research support from Zacharia Thurston and Hyae Ryung (Helen) Kim.

First published by Columbia Business School on 10 September 2025.