The Green Key to Germany’s Economic Recovery

Just as the broader European economy depends heavily on Germany, the continent's industrial powerhouse, Germany's own economy depends on access to affordable power. With geopolitical and climate conditions requiring an urgent transition to renewables, the task now is to develop a politically viable energy strategy.

BRUSSELS – Talk of recession abounds, and it is no secret why. US President Donald Trump’s erratic, beggar-thy-neighbor policies have cast a cloud of uncertainty over US and global markets. Making matters worse, some countries were nearing or undergoing a contraction even before Trump returned to the White House.

One of the largest is Germany, which has been in a recession for two years. While there is no one-size-fits-all cure for Germany’s malaise, most of the biggest challenges facing the new government have a common denominator: a lack of cheap power.

The new US energy secretary, Chris Wright (a former fossil-fuel executive), devoted much of his first official speech to criticizing Germany’s energy transition (Energiewende). As he sees it, Germany was wrong to spend some $500 billion, equivalent to the US spending around $3 trillion, on clean-energy deployment. “Think of how much poorer we would be.” This perspective reflects a fundamental confusion: Wright seems to think that running a country is the same as running a company. It is not.

Government spending in this case is not some dead-weight loss. The economy needs affordable power, and, in any case, such spending will be factored into GDP (though the Trump administration apparently wants to change how this metric is calculated in the United States). Investment in energy infrastructure is just that: an investment, whether the spending comes from the private sector or from government. Almost everyone already accepts that the government has a significant role to play in providing cheap, clean, reliable power.

Far from spending too much, Germany’s problem is that it hasn’t been spending enough. One of the most obvious and important prescriptions for its economy is to relax the constitutional “debt brake” that limits borrowing to 0.35% of GDP. The prior government, with the support of the new chancellor’s party, did so in a big way for defense, with a smaller tranche going to climate priorities, while anchoring its 2045 net-zero goal in the constitution.

That said, Wright did have a point when he criticized Germany’s electricity pricing. German power prices have tripled over the past 15 years and now stand at twice the average rates in the US, and higher than in most other European countries. The reasons are complex – as are the solutions – but one major factor is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine three years ago. That caused fossil-energy prices to spike worldwide, but especially in economies like Germany, which had become increasingly dependent on cheap, piped Russian gas.

High power prices have their uses. They tend to drive more investment in efficiency, which is partly why Germany now consumes around 10% less power than before the start of the Energiewende. Its famously well-insulated windows and other energy efficiency measures are strengths to be celebrated.

But price spikes like those that occurred in 2022 after Putin’s invasion are debilitating, not least because of higher overall inflation linked closely to “fossilflation.” Such spikes sour voters to the green transition, and they hurt industry and the economy.

Green-shoring Industry

Germany and the rest of Europe need more power, not least to build more infrastructure for electrification. Burning less gas, Russian or otherwise, often means using more electricity. Reducing reliance on petroleum implies greater use of electric vehicles, which creates the possibility to use vehicle batteries to help provide grid stability. But overall power demand will go up regardless.

Moreover, the decarbonization of industry has only just begun, and it will be a major piece of the economic puzzle. But to reduce Germany’s climate footprint through “deindustrialization” would be a recipe for disaster. Not only would Germany’s economy be left more vulnerable in the future, but much of its industrial production would simply migrate abroad to places with less robust climate regimes.

The European Union’s famously comprehensive (and acronym-laden) climate policy has one response to this problem. Its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism ensures that imports face the same carbon price as domestically produced goods. The CBAM is an example of a good tariff, because it is specifically targeted to help level the playing field and encourage others to adopt similar climate policies.

Still, it is only a partial solution. The CBAM does not absolve the EU of the need to invest in domestic production, ideally in ways that facilitate industrial sectors’ clean transformation.

In this context, the EU’s recently announced Clean Industrial Deal provides yet another important partial answer. It is a direct response to the dual challenges of addressing climate change and strengthening Europe’s economic competitiveness, as detailed by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi. His report captures the nature of the problem in all its dimensions and demonstrates that economic and environmental goals are not only compatible but mutually reinforcing, provided that investments are steered in the right direction.

Like most big EU packages, the Clean Industrial Deal contains something for everyone. In addition to mobilizing more than €100 billion ($112 billion) in new spending, most prominently in the form of an Industrial Decarbonization Bank, it also stresses the need for lower energy prices through further integration of power markets and looser rules for member states’ subsidies.

Germany should heed this message. The EU has effectively given it a mandate to tackle high electricity prices head on. But this does not mean that Germany should simply rely on increased government spending to lower power prices. An explicit or implicit energy price cap would be the wrong step. Rather, the bloc should seek both further electricity-market integration and pricing reform, while maintaining the right market incentives for renewables deployment and the green transformation.

Overcoming Physical Gridlock

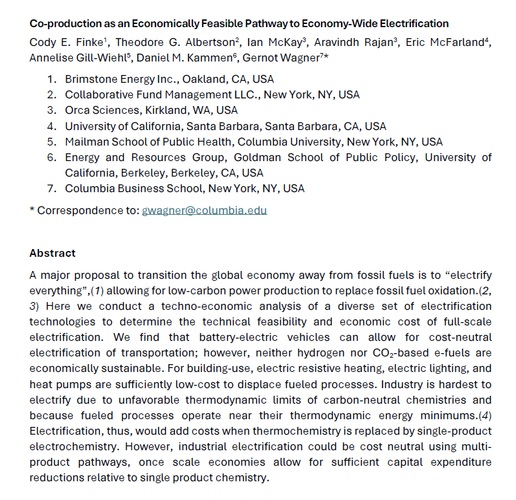

It is tempting to look to Texas, which has become the North Star of electricity-market liberalization. The state recently surpassed California in total solar-power deployment. On most days, a live view of its grid shows that wind, solar, and battery storage provide the majority of electricity – and at rock-bottom rates. After accounting for nuclear, which provides around 10% of baseload power, the state’s power grid often has a smaller relative carbon footprint than those in California or Germany.

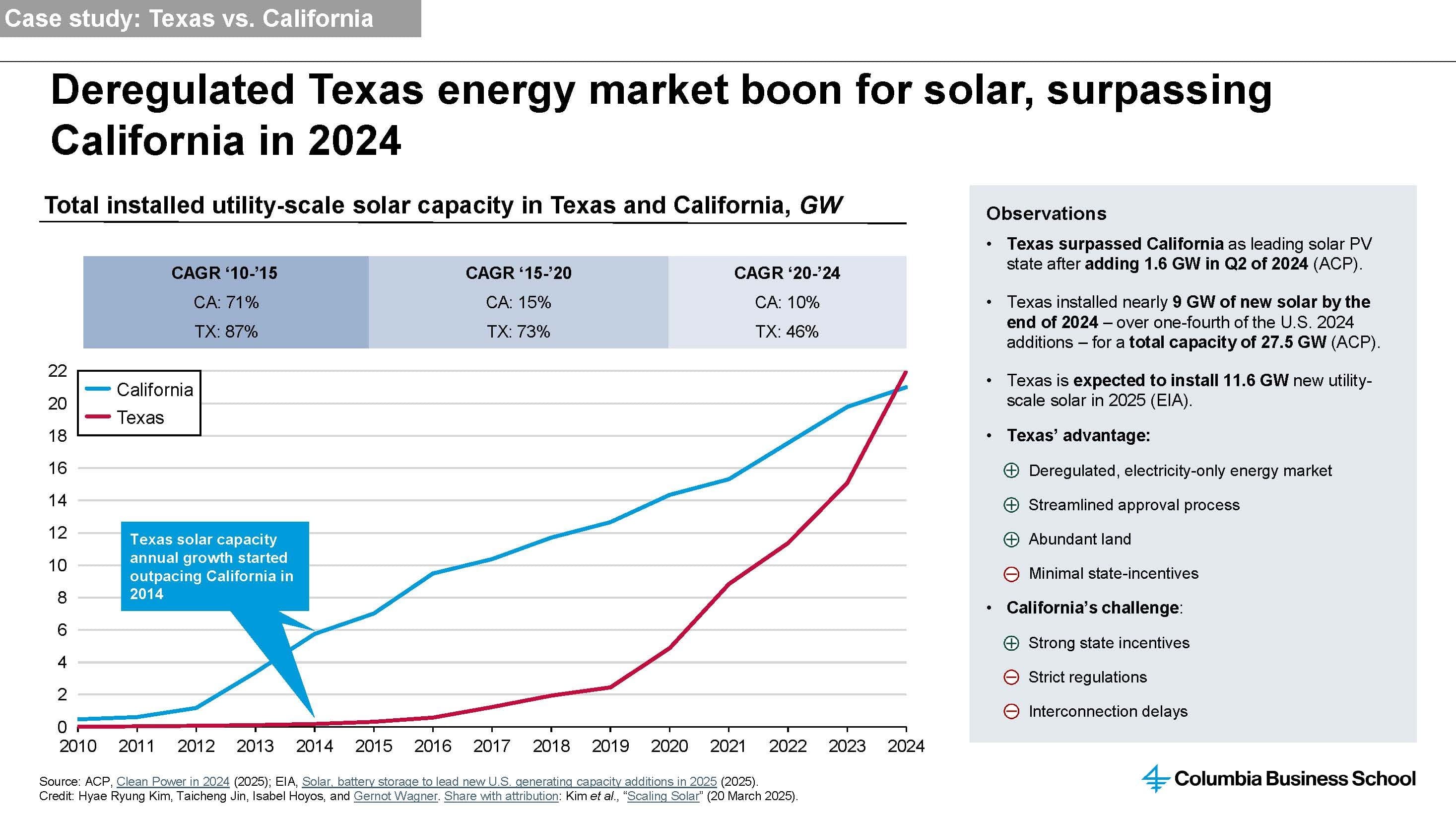

This is certainly not because Texas has adopted ambitious climate policies. Rather, wind, solar, and batteries are now so cheap that it makes economic sense for independent power producers and individual households to deploy them en masse – and they can do so with comparably few regulatory hurdles. Speeding up the permitting of new renewables generation and transmission should be high on the agenda in Germany and elsewhere.

Texas’s power system has its own set of problems. It is overly vulnerable to storms and wildfires, owing to systemic underinvestment in resilience. During those fleeting moments when it faces a Dunkelflaute – no sun or wind – combined with frozen gas infrastructure or heat-related outages, electricity rates can surge to thousands of dollars per megawatt-hour.

For the market to function better in these instances, Texas would need to guide grid investments and, for example, adopt proactive demand-response measures that allow consumers to cut their electricity use when prices are high. In fact, such policies should extend well beyond electricity markets. The state’s lack of an adequate social safety net means that severe price spikes can lead to personal bankruptcy – or worse.

Germany, by contrast, does have a well-functioning safety net, and it does not need to look to Texas for guidance on electricity-market liberalization. Instead, it can emulate its southern neighbor. Germany can look to Austria for further impetus to reform electricity markets and rethink the balance between utility shareholders, ratepayers, and taxpayers, because Austria already derives 90% of its power carbon-free and still experiences some of the same electricity pricing challenges.

Around 60% of Austria’s power comes from hydro dams in the Alps and along the Danube River, and another 30% from wind, solar, and biofuels. The remaining 10%? Still almost entirely Russian gas.

Most of the country’s hydropower is run by Verbund, which has become one of the most profitable utilities anywhere for one simple reason: the bulk of Austria’s dams are decades old, their initial investments long since paid off. The cost of producing hydropower is now extraordinarily low.

And yet, Austria’s electricity prices are not determined by its capacity to generate cheap hydropower, nor wind or solar. Rather, the country’s electricity prices are inescapably tied to the vagaries of gas markets, and this will remain the case for as long as there is even a single gas plant on the grid. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Physically, the task is to break free from not just coal, but also gas; economically, it is to pursue electricity pricing reform head-on.

A Two-tiered Electricity Market

A well-integrated power market has clear advantages, and further expansion and integration of the physical grid is indeed part of the pan-European answer. So are direct investments. Verbund itself has proposed a €100 billion investment plan to boost Austria’s power generation, transmission, and storage capacity. Germany needs comparably larger investments, but taxpayers can’t foot the entire bill; nor can any other single entity. (RWE, Germany’s largest power producer, is reducing its investments rather than ramping them up.)

This brings us back to the rebalancing of costs and benefits between utilities, taxpayers, and ratepayers (from households and small businesses to industrial consumers). Governments in Vienna, Berlin, and elsewhere need to decide who should benefit from cheap low-carbon power, and to what end.

One answer is an explicitly two-tiered electricity pricing system – one for renewables, and one for fossil electricity generation. Solar, wind, and, increasingly, batteries promise to be the cheapest sources of electricity. Making this a reality requires market reform, while keeping appropriate incentives for the necessary investments.

For heavy industry, carving out explicit power purchasing agreements has always been part of the answer. In northern Sweden, Stegra is building the world’s first full-size, low-carbon steel plant. Once operational, it will benefit from large amounts of cheap, clean power (under 2.5 euro-cents per kilowatt-hour) through a long-term contract with the Norwegian utility Statkraft. The company is now seeking similar contracts elsewhere as it aims to expand its presence in countries like Portugal.

German and other European steel companies must follow suit. Many have plans to phase out coal blast furnaces in favor of green hydrogen for primary iron production and electric arc furnaces for steel. The green premium over both coal and gas is real, reminding us that both carrots and sticks matter. Europe’s carbon price is the stick. The carrots so far have largely consisted of direct subsidies financed by taxpayers.

Those subsidies now also go to defense spending, where the security premium will likely be much higher than any green premium ever paid. That alone creates opportunities to use defense and the need for new domestic sources of power to jump-start parts of the green transition. It was no accident that the EU’s clean steel action plan was presented the same day as the “ReArm Europe” defense plan. The steel plan zeroes in on the need for cheap, stable, clean power, including efforts to decouple power from gas prices.

Low-cost, low-carbon power should not be the exclusive preserve of large industrial plants that can sign direct contracts with major power producers. The challenge is to expand its benefits more broadly. Smaller companies and households must also be able to tap into cheap clean power, even if it comes at the expense of utility profits.

Community solar and other so-called “energy communities” formed around renewable energy projects may provide a viable template in Germany and beyond. Prices within each tier would still be tied to traditional “merit order” to provide appropriate market incentives to balance the grid on a daily basis and to invest in new generation sources. The two tiers, meanwhile, allow for the cost savings of low-carbon power to be passed on to consumers. Doing so is essential to keeping the low-carbon transition – and overall economic activity – on track.

Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at Columbia Business School.